A presentation given by Sense of Space Managing Director, Richard Addenbrook to Ilkley Civic Society on the occasion of their annual awards ceremony in March 2013

Thirty years ago, I was studying for my A levels, about to embark upon my chosen career. At that time, Architects enjoyed something of an heroic status, having held the pivotal role in the design and construction of buildings for decades, even centuries. At university, we studied the role of an Architect as Vitruvian man, learning the principles of harmony and proportion, principles which were embedded in the roots of the Renaissance. We had our modern day heroes in Norman Foster, Richard Rogers and James Stirling and I was lucky enough to visit the major exhibition of their work at the Royal Academy in 1986, the like of which has never been repeated.

But the most profound effect on my career and that of all Architects in this country came as a result of a 1984 speech by Prince Charles, although I didn’t realise the significance at that time. Max Hutchinson, former President of the Royal Institute of British Architects commented that Prince Charles, in his famous “carbuncle” speech, had set back the course of Architecture in this country by 25 years although he would probably have preferred to set it back 100 years or more. The result of this speech was devastating for the profession, downgrading the role of the Architect to that of consultant such that Architects, who had in truth become a little too big for their boots, were forced into a more minor role.

On the 25th anniversary of his speech, Prince Charles was invited to address the RIBA for a second time and for me, this invitation demonstrates a new-found resilience in the profession. In his second speech, Prince Charles remarked that he had not intended to start a style war, rather his desire was for Architecture to be community-led. Perhaps someone was listening because four years later, we have The Localism Act and a new National Planning Policy Framework which intends to shift the focus of Planning away from Central Government and into the hands of Local Communities. And Prince Charles, in my opinion, has quite inadvertently managed to strengthen the Architectural profession, causing Architects to become more responsive to the needs of their clients and communities and less obsessed with their own egos.

In trying to arrive at a theme for this talk, I threw around a few ideas along the lines of “Why should I work with an Architect? or “Why should I employ an Architect?” but finally concluded that the question that everyone who is about to commit to an Architectural patronage needs to ask is “What can an Architect do for me?”

It sounds blunt but anyone who is about to plunge their hard-earned cash into a building project has a right to know the answer to this question. I could “toe the party line” here and tell you that the RIBA defines the role of an Architect as “someone who can help you realise your ambitions and guide you through the design and construction process, providing a service that extends well beyond producing a set of drawings, bringing value for money, imagination and peace of mind to your project, whilst keeping it on track and on budget”. This is, of course, highly relevant and for anyone interested, the RIBA website has much more information along similar lines. It is very easy to find at www.architecture.com.

However, for me, there has to be more than this. Seven years of training doesn’t equip Architects with all the skills needed to become anything more than competent Architects. The learning process doesn’t end on graduation day, in fact, it is just beginning. Becoming an Architect can be compared to learning to drive - passing a driving test doesn’t make anyone a good driver. It’s the experience that follows that counts. And in the world of Architecture, there are an infinite number of variables so that no two sites, no two projects and no two working days are ever the same. Learning continues on a daily basis and an Architect’s response to this is what drives the design of buildings and the spaces around them.

At Sense of Space, we start every project with a blank canvas (this being a metaphorical canvas - we do actually draw on computers). We have no pre-determined doctrines, no house styles, no hidden agendas and no standard solutions. Everything is bespoke because we see design as a process. It is a process which needs to respond to the infinite number of variables, a client’s brief and expectations, the nature of a site or existing building, the local environment, the global environment and they way in which people will interact with the building in such a way, we hope, that the design will enhance people’s lives. The result of this is that all our projects are different - we believe it is quite difficult to spot a “typical” Sense of Space design. From a client’s perspective, the process represents a journey of discovery - we see ourselves as “enablers”, guiding and advising but not forcing a client to go down a route which makes them uncomfortable.

We believe that if we get the process right, then good design should follow. Our approach is not a stylistic approach but one which requires an understanding of what makes buildings and spaces life-enhancing, together with an appreciation of proportion, rhythm and harmony. Even if the Architecture of the Modern Movement is not your ideal, it is important to appreciate that the greatest exponents of the International Style such as Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius had as full an understanding of the importance of proportion and harmony as the great Classical Architects such as Palladio, Michelangelo and Brunelleschi. For me, my moment of epiphany came in 1988 when I visited the surviving buildings of the Weissenhofsiedlung exhibition in Stuttgart. Built in 1927, the Weissenhofsiedlung included projects by the “avant-garde” of modernist architects. It is essential to draw the distinction between these fine examples of their time, some 85 years old, and the numerous dreadful copies of the sixties and beyond. My key point here is that it is quite acceptable to be a fan of both Modernism and Classical Architecture, but only if they are done well.

To illustrate my point, I would like to show you these two images: the house on the left is a 1960’s estate-type house, typical of tens of thousands of speculative developments which were completed throughout the country; the house on the right is a Georgian villa with well proportioned openings and a clear sense of entrance.

In fact, they are the same building: the image on the left is a “before” view, the image on the right is “after”. When designing the alterations to this house, we went to great lengths to understand the contextual nature of Georgian Architecture, studying pattern books so that we could appreciate the way in which proportion affected the dimensions of the building, in spite of the technical challenges this presented. As the RIBA document states “this is a service that extends well beyond producing a set of drawings”. I can honestly say that I am a fan of this type of approach, if it is done well. By contrast, I am not a fan of the “pastiche” which seems to dominate the current new housing stock throughout the UK.

Moving away from the past and looking forward, what are the challenges we face when considering the future of Architecture in this country and how can an Architect embrace such challenges and seek new opportunities? Many people are aware of the highly publicised changes to Planning Legislation, resulting in the introduction of a new National Planning Policy Framework – 50 pages of legislation to replace over 1000 pages of legislation with some grey areas in between. As the new NPPF has just reached the end of its 12 month honeymoon period and the spectre of a “presumption in favour of sustainable development” looms if Councils don’t get their acts together, no one really knows what the next few months will bring. Only today, I read that the Planning Minister has indicated a massive u-turn in respect of the presumption in favour of sustainable development. The important fact is that Architects (and indeed, anyone who is involved in the design and delivery of buildings) keep fully up to date with any such changes to legislation. Of course, it may not all be bad and opportunities may arise where great examples of Architecture come forward.

Fewer people are aware of the fast-approaching changes to the Building Regulations and in particular, the drive towards zero carbon. This subject area is massive but if it can be summarised, the Government has reaffirmed it commitment for all new dwellings to be zero carbon by 2016 with all other new building types to follow two years later. For the UK construction industry, this is a quantum leap forward and is likely to make traditional construction methods obsolete in the very near future. The move towards zero carbon dwellings is being driven by the Code for Sustainable Homes and the Building Regulations are being amended in line with these changes, the next big amendment being at the end of this summer when the energy performance requirements for new dwellings (and probably extensions and works to existing dwellings) will become much more stringent. As an environmentally conscious practice, we support this move, after all, we have been designing super-insulated, energy efficient buildings for years. However, if you are in the process of moving a development forward, it may make sense to get your Building Regulations application registered before the end of the summer.

The counter to all of this is of course, the economy and good designers will need to find ways of balancing improvements in the fabric of buildings with tight budgets. Some believe that a more standard approach should be adopted and the introduction of Building Information Modelling is a move towards making the construction industry more like the automotive industry where Architecture becomes commoditised. I remain relatively sceptical about this approach for the majority of projects although we are currently looking at the potential for a modular approach to house extensions.

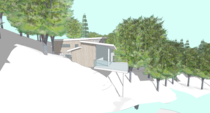

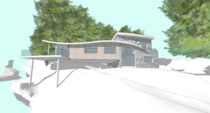

As sustainability is important to us, I just want to show a few images of a low energy and highly sustainable project we carried out in Ilkley for which we were very happy to receive a previous Civic Society Design Award. Our approach with all such projects is to focus on the passive elements of design such as super-insulation, orientation and the creation of a very well sealed building envelope. This house has 240mm of insulation in the walls and roof, is triple glazed and orientated to achieve maximum benefit from solar gain with respect to free heating and a reduction on the demand of artificial lighting. The approach to sustainability is fully integrated with the design – each is dependant upon one another. The addition of a few renewables has resulted in a house which has a very low energy demand.

As far as the future is concerned, we will continue to support our clients by designing highly sustainable, energy efficient buildings and in the case of projects such as this, on challenging sites. We are very grateful to the Civic Society for offering their support with respect to this project – unfortunately, we were not able to convince the powers that be and the planning application received a refusal. In hindsight, we were proposing the loss of a number of trees, in order to preserve the remainder of the wood which populates this site and we accept that the concept of losing trees in order to protect other trees is a difficult concept to come to terms with (although, the growing support for large tree buildings in North America which lock trees into buildings such that they cannot be removed is, in my opinion, something that we could learn from in this country).

I regularly provide information on subjects which are relevant to our work via a number of different channels such as Twitter and Facebook and the links to these can be found on our website. We are also pleased to promote our free 30 minute consultation service which we hold on Tuesday afternoons for anyone who is thinking about a project but would like to get a feel for what they can expect before taking the plunge.